The battle over whether the National Credit Union Administration should be given supervisory powers over third-party vendors rages on, with no end in sight—unless Congress chooses to step in.

The NCUA and the Federal Housing Finance Agency are the only financial regulators that do not have the power to supervise vendors working for financial institutions. NCUA board members, the agency’s Inspector General, the Government Accountability Office and the Financial Stability Oversight Council have asked Congress to give the credit union regulators that power, but to no avail.

Credit union trade groups, on the other hand, have opposed granting the NCUA the right to examine vendors, in part because they anticipate the agency will need more money to hire specialized examiners. That additional money could result in credit unions having to pay additional fees to the NCUA. They also contend that the agency can get the information it needs from other regulators.

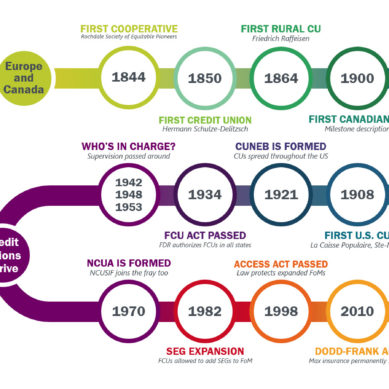

The NCUA once had vendor supervisory powers—at least temporarily. In the late 1990s, there was a great deal of handwringing over whether computers would be able to distinguish dates correctly in 2000, an issue that became known as “Y2K.” As a result, Congress granted the agency power to oversee vendors. However, that power was only temporary, between 1998 and 2001.

On several occasions, Congress has considered renewing the authority. But that has not occurred, much to the NCUA’s chagrin. It is not for a lack of trying.

In 2022, the House version of the annual defense authorization bill included a provision calling for NCUA vendor authority, but the eventual House-Senate conference report omitted it. That same year, legislation was introduced in the Senate, by Sens. Jon Ossoff, D-Ga.; Mark Warner, D-Va.; and Cynthia Lummis, R-Wy., to grant those powers to the NCUA. That bill went nowhere in the Senate.

On the other side of the Capitol in 2022, the House Financial Services Committee, then controlled by the Democrats, approved legislation, 24-22, giving the agency the power to audit vendors. All Democrats voted for the bill and all Republicans opposed it. The bill was never considered by the full House. With the Republicans now controlling the House, the bill has not resurfaced.

Last year, Senate Banking Committee Chairman Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, told those attending the Credit Union National Association’s Government Affairs Conference that he favored giving the NCUA vendor authority. However, as in past years, nothing happened.

As the debate continues unabated, here is a handy guide to the arguments on both sides of the issue.

Pro

NCUA Chairman Todd Harper, at various times, has referred to the lack of vendor authority as an “Achilles’ heel” and a “regulatory blind spot.” Most recently, Harper made the case for vendor authority in a speech at the Brookings Institution. Shortly after that speech, NCUA Inspector General James Hagen issued his annual “Top Management and Performance Challenges” letter to the agency board, again saying that Congress should give the agency such powers.

Both made similar arguments; here is what Harper had to say.

Increasingly, credit unions are using vendors for such activities as loan origination, lending services, Bank Secrecy Act compliance, or money-laundering services. The pandemic accelerated the credit union industry’s move to digital services, increasing the industry’s reliance on third-party vendors. Member data is stored on vendors’ servers and some of those vendors may not be using industry-accepted cybersecurity protections.

“The NCUA’s lack of visibility into these critical industry participants is a major problem in that it poses a systemic risk to the financial services system and our national security,” Harper said during his Brookings Institution presentation.

In addition, there is a concentration risk since five core banking processors handle more than 90% of the credit union system’s assets, the chairman said. That is a real risk, according to Harper.

Harper argued that the problem is not just theoretical. In November, 2023, the NCUA received cyber incident reports from several small credit unions saying that their core service provider had been experiencing system outages. Dozens of credit unions with aggregate assets of almost $1 billion experienced outages or disruptions during this one incident. The problem affected almost 100,000 members.

“The fallout of this cyber incident demonstrates how a single vendor’s problems can quickly metastasize into crisis for credit unions, members, and the overall system,” Harper said, adding that the lack of vendor authority hampered the agency’s efforts to respond to the situation.

The NCUA’s inability to examine Credit Union Service Organizations also has had an impact, the chairman said. The agency’s Inspector General has reported that between 2008 and 2015, nine CUSOs contributed to material losses to the agency’s Share Insurance Fund. One of the CUSOs caused losses at 24 credit unions, with a number of those credit unions eventually failing.

In 2023, the NCUA issued a final rule requiring credit unions to report cyber incidents within 72 hours of discovery. Within the first 30 days of the rule becoming effective, the agency received 146 incident reports, with about 60% of them involving third-party servicers.

Con

Before they merged, the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions and CUNA each separately argued against granting the NCUA supervisory and examination powers over vendors and CUSOs. Much of their arguments boiled down to money.

The trade groups said that implementing the new authority would require significant expenditures by the agency, with the costs being borne by credit unions and their members.

The NCUA already sits on the Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council, which includes other banking regulators. The FFIEC was created to coordinate examination findings and eliminate duplication.

“Granting the NCUA authority over third parties will provide no clear benefit to credit unions and their members but will result in duplicative regulation as other federal agencies already compile and can share this information with the NCUA,” NAFCU contended in a policy statement.

Instead of granting the NCUA vendor examination authority, the agency should use the FFIEC to gain access to information about the other agencies’ vendor examinations. If the other agencies refuse to give the NCUA access to those reports, Congress could compel the council to provide them.

Since the NCUA said that five core processors serve such a large percentage of financial institutions, the agency is likely to find the data from other agencies to be applicable to credit unions, the argument goes.

When it comes to CUSOs, since they are owned by credit unions, the NCUA already should be able to gain access to needed data. NAFCU noted that the agency has used this authority to ask for data in the past and has not provided details about how the current authority is insufficient.

In 2022, CUNA sent a letter to Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., one of the sponsors of Senate legislation that would have granted the NCUA supervisory powers over vendors. The letter asked Ossoff to reconsider his sponsorship of the bill. CUNA said that the agency has exercised effective supervision of CUSOs and servicers and called the legislation a “solution in search of a problem.”

“Presently, the agency has virtually limitless authority to request information regarding CUSOs from the credit union owners of the CUSO; and, the agency has broad authority to adjust the due diligence expectations credit unions must satisfy when engaging third party vendors,” CUNA President/CEO Jim Nussle wrote.

As NAFCU had argued, Nussle went on to say that the new powers would require the hiring of specialized examiners, adding that if Congress were to give the NCUA supervisory powers, the agency should make a commitment to cut its budget elsewhere to pay for the additional staff.

Nussle said that as of 2022, the NCUA had not developed a clear vision of how it would exercise its new power if Congress provided it. “It is therefore impossible for us to assess the impact it would have on credit union operations, including whether it would lead third-party vendors to increase the costs credit unions pay for their services.”

He added, “Sharing details of their intentions with Congress and the industry is necessary to us understanding what to expect if NCUA is granted this authority, and it could help allay some of our concerns.”

Nussle indicated that despite CUNA’s reservations about granting the NCUA examination powers, the trade group could support changes to the Bank Service Company Act to ensure that the nation’s information security apparatus is as strong as it needs to be to fight cyberattacks and data breaches.

What to expect in 2024

If Congress gives the agency third-party vendor examination powers, how would the agency use them?

Here’s how Harper explained the agency’s plans during his Brookings presentation: “When the NCUA is given this authority by Congress to complete its job, it will implement a risk-based examination program for third-party vendors focusing on services that relate to safety and soundness, cybersecurity, Bank Secrecy Act and Anti-Money Laundering Act compliance, consumer financial protection, and areas posing significant financial risk for the Share Insurance Fund. In short, the time has come to close this growing regulatory blind spot.”

But so far, there is no indication that Congress is willing to agree to Harper’s request.