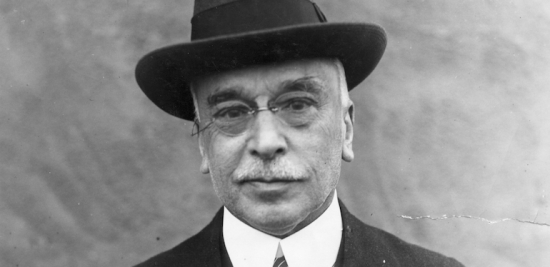

Many may recognize Edward Filene’s name from bargain store Filene’s Basement, but his influence extends far beyond retail.

Credit unions in the United States serve over 100 million members and control $1 trillion in assets. There are 5,174 credit unions in the United States, employing over 225,000 people. They line Main Streets and suburban thoroughfares.

Yet, the first American credit union was only established in 1908. That makes American credit unions younger than some of the world’s oldest living people. What could account for their astonishing growth over the 20th and 21st centuries? The answer comes down to the Father of American Credit Unions, Edward Filene.

Early life of the Filene family

Edward Filene was born in 1860 in Salem, Massachusetts, to William Filene and Clara Ballin. William sold women’s clothing and dry goods. He oversaw a succession of shops in Massachusetts and then New York. The post-Civil War era economy was volatile, and by 1869, the Filenes had nothing but each other. After their unsuccessful New York venture, they relocated to Lynn, Massachusetts and settled in a working-class neighborhood. William set up a small women’s wear shop, positioned so the factory girls could walk past on their way to work.

Location changed everything. The store experienced so much growth William was able to expand to three stores by 1875. Clara handled accounts while Edward and his four siblings handled customer service. Harvard accepted Edward in 1880, but William suffered a stroke the same month. Edward and his brother, Abraham Lincoln (A. Lincoln) Filene, took over operations. William remained de facto manager.

The brothers expanded to Boston in 1881. They opened a 24-square-foot store in the shopping district. While the previous stores focused on serving working customers, this store catered to the city’s middle class. By 1883, they had opened another location. Both stores pulled in $100,000 per year ($2.6 million in 2020 dollars). By 1890, the Filenes sold off the three New England stores to focus on the Boston operations. They invested the proceeds into a five-story building on Washington Street. Filene’s became the largest women’s wear store in the city.

By 1891, William handed the reins to Edward and A. Lincoln. They incorporated the business to William Filene and Sons. They sold Fancy Goods and Women’s Ready-to-Wear Apparel. The store, later shortened to “Filene’s,” experienced exponential growth. It became New England’s largest retail store.

Building a solid foundation

At this point, you may be asking, “That’s great, but what does all of this have to do with credit unions?” The answer lies behind the scenes. The Filene brothers, especially Edward, passionately advocated for their employees.

Edward instituted:

- profit-sharing

- a living wage for his employees (including women)

- a five-day, forty-hour work week

- health clinics

- insurance

- paid vacations

He introduced the Filene Cooperative Association, a company union (a union under one employer, as opposed to a trade union). He hoped this would encourage collective bargaining and arbitration between employees. The nascent cooperative banking movement in Europe and Japan dovetailed Edward’s policies.

Edward visited Calcutta, then colonized by the British, in 1907. The leader of Bengal’s cooperative credit societies, William Robert Gourlay, took Edward on a tour of rural India. Gourlay explained the operations of the local Agricultural Cooperative Banks. A group of villagers deposited their savings. Then, the colonial government would lend that amount to the group. The group was then able to disburse this loan to its members.

Observing these cooperatives galvanized Edward. He brought the idea to his friend, Theodore Roosevelt. Edward suggested the United States try cooperative banking in the Philippines, then a colony. Roosevelt expressed interest, but nothing came of it. This did not deter Edward.

Edward spent the 1910s campaigning for public transportation and workman’s compensation. Still, he kept an eye on the introduction of credit unions in American society.

The creation of the first credit union

Alphonse Dejardins had opened a “People’s Bank” in Quebec. His “caisse populaire” was the earliest credit union on the continent. Filene invited Desjardin to Massachusetts with Pierre Jay, the banking commissioner of Massachusetts. They collaborated on the Massachusetts Credit Union Act of 1909. It was the first comprehensive credit union legislation in the U.S.

Jay and Filene came up with the term “credit union.” Filene chose “credit” to dissociate from predatory consumer loans. They selected “union” to show solidarity with workers.

Chip Filson#1

A very well written summary of early cu history. Like the idea of telling the cu story around one of the founders and his journey. Would be interested in how long the article took to write and the sources used.

Any lessons for today about leadership from Filene’s efforts?

Have you considered writing a similar 50 year story on CU*Answers?