Read more at chipfilson.com

Over the weekend banking regulators closed two banks, the $206 billion Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and the $110.4 billion Signature Bank in New York.

The precipitating events were runs by depositors. In each bank over 90% of depositor funds exceeded the FDIC’s $250,000 insured limit.

Earlier in the week SVB announced its intent to raise additional capital after reporting sales of long-term treasury securities at a loss of several billion dollars. The bank had a significant duration mismatch between its customer deposits and long term treasury investments when the Fed began its monetary tightening in March 2022.

The bank is reported to have lost over $40 billion in deposits sparked by social media posts (a “Twitter run”) advising the bank’s tech startups and venture funds to withdraw their deposits.

Signature Bank had a concentration of business with crypto clients and legal firms and was likewise vulnerable to large deposit outflows.

The banks’ failures will erase all shareholder and debt capital. Depositors balances will be insured in full and available for immediate withdrawal. The FDIC as conservator will attempt to find buyers for the books of business, and so intends to keep operating their services. Any losses from the resolution of the banks will be paid by the FDIC through its assessments on the entire system.

More than a problem bank rescue

To prevent a system wide financial crisis—a contagion—from occurring in institutions with similar balance sheets of underwater securities and high amounts of uninsured deposits, the regulators announced a special lending program for all banks.

Loan terms will be up to one year, not the normal 90 days. The amount borrowed can be the par, not market value, of pledged securities (no haircuts).

This will give banks time to work through their duration mismatches by raising more capital or portfolio rebalancing. The cost of borrowings will be high. Earnings may be adversely affected if loans become a large source of funds.

The quick action by the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury is intended to prevent a loss of market confidence leading to panicky withdrawals from regional banks which have comparable balance sheet situations.

What does this mean for credit unions?

Before this weekend, liquidity was growing tighter for all credit unions. Share growth reversed in the second half of 2022.

The early results from 2023 show continued deposit challenges. Consumers are once again learning about the returns and liquidity in money market funds.

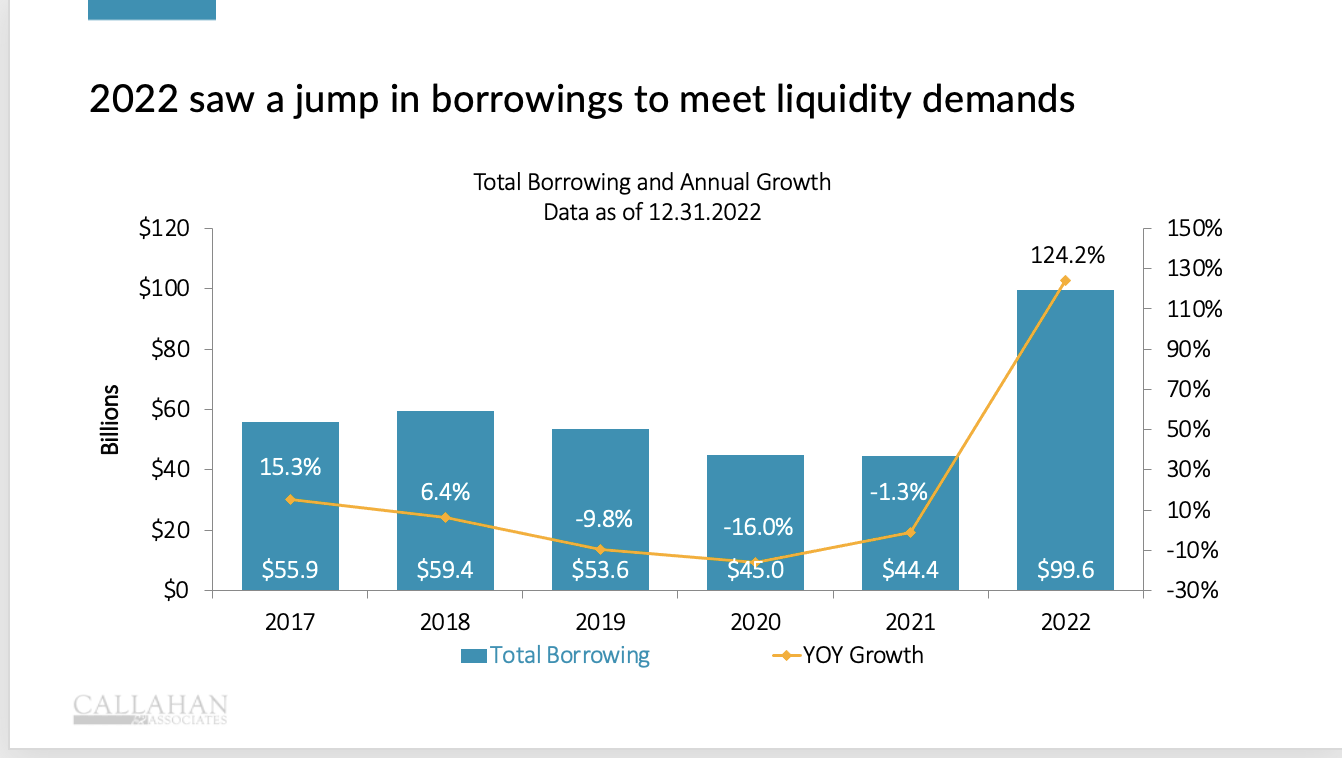

As reported in 2022 year-end numbers, 1,193 credit unions had borrowed a total of $99.6 billion, or 4.6% of total assets. Within these totals 797 credit unions reported $92.3 billion from the FHLB system, up 318% from the year earlier.

Source: Callahan & Associates

In contrast 436 credit unions reported loans of $2.3 billion from the corporates. Several corporate CEO’s reported that their overnight short term settlement loans had risen from only a couple of dozen a year ago this time, to over 250 per day in the recent months.

In Callahan’s Trend Watch call for Q4 2022, a whole new section of charts portrayed the system’s changing liquidity picture: the drawdown of investments and increased levels of external funds. The presentation reported that borrowing credit unions’ loan-to-share ratio was 82%. For those without borrowings, the ratio was 58%.

The risks for credit unions

Credit unions are part of the country’s financial system. If consumers or the public begin to doubt the system’s reliability, these concerns will also affect credit union members. This is the fear of a financial “contagion” which the Fed’s borrowing plan is meant to forestall.

For example, I was sent an email from San Mateo Credit Union to its members on Friday afternoon after the SVB failure. It read in part:

Dear member name,

Amid today’s news of the closure of Silicon Valley Bank, I want to take this opportunity to assure you that San Mateo Credit Union (SMCU) remains safe, sound, highly liquid, and in excellent financial condition.

Our financials as well as our investments are structured very differently from Silicon Valley Bank. As one of the top performing community financial institutions in the state, SMCU has a very solid liquidity position. . .

Some of the same balance sheet factors causing these bank failure are present to a limited degree in several credit unions. These factors include underwater securities, duration mismatches with longer term loans, and a potential for an ROA earnings squeeze competing for funds.

The advantage credit unions have versus these failed banks is there are minimal amounts of uninsured deposits versus the 90%+ they held. The vast majority of credit union core deposits are “sticky”, unlikely to run off at a Twitter post.

Like banks, credit unions have yet to see a major uptick in problem loan credits. These failures were not from credit defaults.

Rather, investments and loans were made in a low cost of funds environment that now look less sound. The resolution of these situations will depend on how the broader economy trends.

Learning from the FDIC, Fed, and Treasury

A major gap in the credit union system is the coordination and use of NCUA resources supplied by credit unions. The federal or state banking regulators worked in common to respond to specific incidents and create a systemic plan to manage potential ongoing concerns.

Even though the cooperative regulatory tools are managed by a single NCUA board, they have not been positioned for a similar response.

The first line of liquidity mobilization for credit unions is the corporate system. However its lending ability options are severely limited by regulations imposing balance sheet duration caps and funding options from 2010. Less than 2% of borrowings at December 2022 were from corporates.

The second most important source of funding is the FHLB system, eleven cooperative institutions that are directed and owned by their members. There has been no comparable credit union operational partnerships or planning with the Central Liquidity Facility. The CLF has not had a loan outstanding since 2009.

NCUA board members have called out Congress for failing to extend the CLF’s COVID era borrowing and membership flexibility. But it is unclear how those reinstatements would make the CLF any more relevant than it has been in the past.

The CLF is supposed to be a public/private partnership, but the reality is one sided. NCUA seeks more credit union members’ shares, but wants to retain all say in how the facility is used and any programs developed.

Finally, the NCUSIF has fallen prey to the same duration misjudgments as the failed banks.

As of January 2023, only 7.7% of the $21.8 billion fund was in cash. The fund’s average weighted maturity was over 3.2 years. Its market, or immediate liquidity value, was below par by over $1.1 billion.

The credit union system was built on multiple forms of self-help and self-financing—not private capital or government funding. Capital from retained earnings acts as a financial “governor” on ambitious growth plans. The NCUSIF and CLF (when operational) were jointly designed and cooperatively funded. The system did not rely on taxpayer resources or bailouts as credit unions are exempt from federal taxation.

In addition to the cooperative FHLB model and this past weekend’s federal regulatory coordination, there is another lesson for credit unions.

The FDIC and Fed stepped in with funding to save these institutions’ operational capabilities so that customer payrolls and transactions could continue as normal. Ultimately the regulators are seeking a buyer for the firms’ business customers. And as noted by one commentator, to make a profit on the situation.

This approach minimizes any loss to the FDIC while continuing service to customers, some of whom have relied on these institutions for decades.

The overriding unsettled issue

The prospect of a “financial contagion” may have been stopped. Time will tell. The overriding issue is what will the Fed continue to do now with rates: keep raising them or pause? How will the greater caution these events imply for the financial community affect the economy? How will the possibilities of a slow down, continued growth, or possible recession emerge?

While institutional stability may have been achieved, the longer term economic and rate outlook is still uncertain.

History may be useful in this uncertain moment. The previous largest bank failure ever of Penn Square in 1982 was just a prelude to a much wider bank and S&L culling. And the 2008 Lehman and Bear Stern failures led to a period of extended “market dislocations” in terms of securities valuations and market transactions.

In one case the system responded with no failures even though over 80 credit unions and banks had uninsured deposits in Penn Square. The CLF stepped up with loans, the insurance fund was redesigned, and NCUA examiners assisted in workouts.

In the second crisis, NCUA went forward without credit union input, just assessments. Two years after the 2008 financial failures, it created a credit union specific crisis in September 2010 by liquidating five corporates. That resolution continues on 13 years later. Surplus payouts are approaching $5 billion as opposed to loss projections of $13.5 to $16 billion for the system when the liquidations commenced.

In one case the agency worked with credit unions for solutions. In the latter one, it did not. Should there be credit union difficulties this year, that difference in approach will be critical to retaining member, credit union, and public confidence in a separate cooperative financial system.