While at a conference recently, a credit union CEO was discussing his credit union’s new online-only charter expansion with me. As he highlighted the new features the digital credit union would offer and what services he was planning on adding in the next few years, I found myself wishing the credit union was closer so I could qualify for its field of membership.

Because despite being a digital-only offshoot of the credit union’s original charter, the new credit union did not have a field of membership that extended to meet the potential of the online credit union. The credit union was limited to servicing a number of counties in their state. While I’m sure the NCUA could provide a list of regulatory reasons why a Michigan resident could not join a digital credit union states away, it was definitely a disappointment.

This particular example is merely one instance of an ongoing issue in the credit union industry: despite the leaps in technological capabilities and the shift in society toward digital services, the credit union field of membership system still bases its requirements on geographical location, assuming a traditional, in-person experience.

But the original decision to create such field of membership standards was due to circumstances of the time, and as such, isn’t it time they were altered to meet a more modern era to better serve both credit unions and members? Or do the original boundaries set still offer purpose? Does a field of membership keep credit unions tied to their communities and promote one of credit unions’ founding ideologies? Or have they become needless restrictions for both credit unions and members alike?

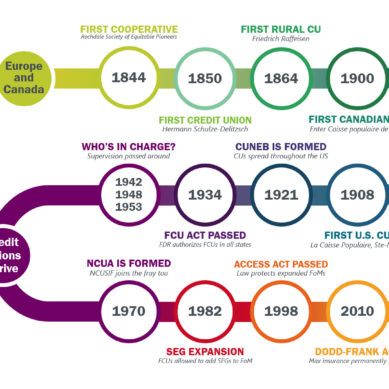

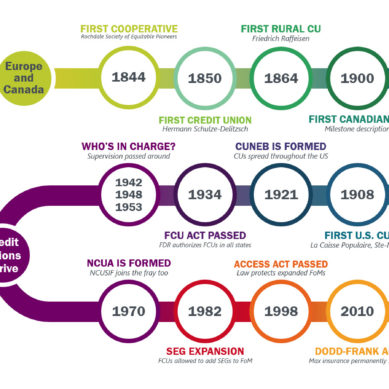

The history of field of membership

In the early years of the credit union industry, credit unions were often founded on humble origins. Typically, a handful of people in a shared community worked together in an effort to provide for those in need and create a financial institution that benefits them all.

TruNorth Federal Credit Union, for instance, was founded by eight neighbors sitting around an orange barrel outside a local store, working to pool together $35.

These first credit unions were obviously very localized as the stakeholders were neighbors and the intent of the credit union was to provide for said neighbors. Additionally, a lack of means prevented people from traveling long distances, so their range of choice for financial institutions was limited.

Field of membership at the time was not so much something official you had to qualify for, but simply a result of the time, as credit unions had limited reach and the everyday member had limited travel capabilities. The credit union was in the community and the community had the credit union.

As the decades passed, cars became more commonplace and affordable, people’s everyday reach increased, and their options for financial institutions widened as well. In response, the field of membership became more official, and new members looking to join a credit union had to fit certain requirements.

These requirements varied based on the credit union and its established field of membership rules, but there are typically three types of fields of membership:

- Community-based: people living, working, going to school, or worshipping in one common area.

- Occupational: people working for the same company or in the same industry.

- Associational: people belonging to a specific group, union, church, etc.

In the 100+ years since credit unions began, the industry has changed nearly everything about the way they operate. From how members deposit, withdraw, cash checks, check their balance, apply for loans, open a new account, and more, nothing has stayed the way it was originally designed. Field of membership, however, has mostly remained stagnant and firm in its restrictions—though the rules have allowed for interpretation in dire situations.

Past is prologue

One example of such a dire situation resulting in change occurred in 1982. The requirements—though not necessarily changed—were interpreted more liberally in 1982 to support credit unions and their members. The changes had a drastic effect on the industry as a whole.

During the early 1980s, many industrial plants, hospitals, and companies closed due to the recession. As a result, the credit unions that serviced those employees were often forced into liquidation, leaving members out of luck. Mergers were denied because, at the time, employee-based federal credit unions could only service one location. Meaning that when the Veteran’s Administration hospital closed, the hospital’s credit union in Baltimore was unable to merge with a similar credit union in Washington, because field of membership restrictions stated they didn’t have a common bond.

1981 marked the largest decline in operating federal credit unions on record with 471 closing, beating out the previous year’s record of 298. Out of the 471 that closed that year, 397 of them were occupational credit unions. It was clear something needed to be done to prevent the numbers from dwindling further. One group—consisting of Ed Callahan and Bucky Sebastian—pushed for a more liberal interpretation of the 1934 Federal Credit Union Act, arguing that employee credit unions could “serve more than one group as long as each group had its own common bond.”

As a result, the NCUA revised field of membership rules to allow the merging of employee-based federal credit unions with credit unions that had differing common bonds. The result of that slight change was astounding. Many credit unions were saved from liquidation, demands on the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund were reduced, and barriers to entry were lowered, making it easier for groups to become credit union members.

Unique needs meet unique offerings

So what’s the takeaway from the above example? If anything, it proves that change (particularly in regard to field of membership) can reinvigorate the credit union industry as it did in 1982. Perhaps it’s time for history to repeat itself.

Especially now, as physical limitations are essentially nonexistent and physical credit union branches are making the shift from teller lines to ITMs, what purpose do these particular rules for fields of membership serve? Why set such strict geographical limitations on who can utilize a credit union if the credit union and the member both have the capability to work together regardless of location?

No two credit unions are the same, and neither are their services, rates, and products. At the same time, no two members are the same either. They have different needs, credit histories, and goals. While one credit union may be the perfect match for a member, it may be lacking something another member needs.

That member’s perfect match of a credit union—fit with the exact services, loan rates, and offerings the member is looking for—probably exists, but if it is located even just a few cities over, the member may be unable to qualify for the credit union. In this instance, they may need to settle with a credit union (or bank) that doesn’t suit their needs as well, limited by physical location, despite the fact that this member has not stepped foot into a branch of any financial institution in years, and is unlikely to do so even after opening their new account.

So who exactly does the field of membership system benefit in this instance? The member and credit union both lose out, without much of a justification as to why. And now, as specialized digital financial institutions crop up, with no location-based fields of membership, they showcase how limited common bonds that rely on distance truly are. These financial institutions have proven that a regional approach no longer best serves the everyday consumer’s needs. Instead, identity or relationship-based common bonds offer products and experiences that speak more to who the member is rather than where they live.

Serving the underserved

The above is particularly important for underserved and underbanked communities that find themselves unable to fit into the traditional banking mold. As they work to find institutions that meet their needs, they may be turned away from credit unions that can best serve them simply because they are not in that credit union’s geographical region.

LGBTQ, immigrant, and Black and Latino communities for instance are relying on digital financial institutions to work with them on issues such as limited credit history and as a means to solve the distinct lack of credit unions and banks in their areas. (You can read more about that here.)

These situations are ripe with opportunities for credit unions, not only as a means to find new members and grow but as a chance to offer their products and services to areas and communities that are statistically underbanked and underserved. However, if the credit unions that can do so are held back by location, they face greater barriers to being able to take advantage of those opportunities.

It seems foolish to deny a credit union the ability to serve those potential members, regardless of where they are located. If a credit union out of Florida has the digital capabilities to provide services for underserved areas of New York, for example, what benefit is there in preventing that? Particularly when there are proven successes, such as Superbia Credit Union, that show specialized credit unions that have relationship and identity common bonds can operate within regulatory parameters set by the NCUA.

How can they be altered?

All this to say that while fields of membership may still be essential to the credit union ideology, the current requirements (community-based, occupational, associational) are without a doubt outdated and desperately need to be updated, or we risk becoming outdated along with them. But how can we correct them to better reflect where our industry is and better meet the credit union promise of “meeting members where they are?”

A Filene Research Institute report from 2020 on this issue came to the same conclusion, noting that current requirements do little but hinder both credit unions and members. The report argued not for the dissolution of field of membership, but for a shift in the definition and three types of membership.

The author of the report, Andrew Turner wrote, “Although central to the credit union identity, fields of membership present an ongoing source of tension and conflict because there is no consensus on why they exist anymore. Traditional field of membership designations—community, association, occupation—no longer correspond to modern citizens’ identities or their understandings of the groups to which they belong.”

Turner recommends three new common bonds in place of the current ones: a relationship-based common bond, an identity-based common bond, and a membership-based common bond. These suggested new common bonds solve the issues mentioned above and offer a more modern approach to pairing credit unions and members than the current antiquated system. The suggested new bonds also further cement the idea that credit unions should be focusing on who their members are instead of where they are.

Connection to the community

Now, some may argue that rigid field of membership requirements keep credit unions central to their communities. After all, the very foundation of credit unions as discussed earlier, was built upon the idea of neighbor helping neighbor. If members are bypassing their local credit union in favor of one across the country, and the small-town credit union doesn’t actually have many members from its small town, then is the connection between credit union and community severed?

Well, no. Because serving the community does not simply mean serving only the parts of the community that have verified credit union members. It means working in all parts of the community both for the betterment of it and to create a bond between the credit union and the people in the community they are located. Regardless of how many or how few members a credit union has in its town, it should still work to be a pillar of that community.

Furthermore, if the shift in recent decades toward self-service—which has resulted in fewer tellers, traditional branches, etc.—and the 2020 pandemic, during which most credit unions were completely digital, didn’t break the bond between credit unions and their communities, altering field of membership bonds certainly will not. The industry has proven that the credit union ideology can hold up even when credit unions are in a long-distance relationship with their members.

From past to present

Members can—and should—be picky when it comes to selecting their financial institution. They should always select the one that offers them the best chance of financial success as it fits their specific needs, unrelated to where they or the credit union are located.

Whether that comes down to having a specialized product offering or simply better budgeting tools and online interfaces, in this day and age, why should members be settling for an institution that doesn’t work for them? The truth is, and is increasingly so, that members and non-members alike won’t settle. They will find another institution—be it bank, FinTech, or otherwise—that can meet them where they are.

While credit union technology and services reflect the preferences and needs of the modern, everyday member, the field of membership common bonds do not. They set limitations on credit unions and members alike and do more to hinder than help. The rest of the industry has evolved since our founding, it is time for field of membership to do the same.