Read more at chipfilson.com

Who pays for your rewards? That was the question posed by a Federal Reserve study released in December 2022. Their short answer is “sophisticated individuals profit from reward credit cards at the expense of naïve consumers.”

The Federal Reserve study describes this outcome as a redistribution of wealth. They calculate the result as an “aggregate annual redistribution of $15 billion from less to more educated, poorer to richer, and high to low minority areas, widening existing disparities.”

The full study is 84 pages, but the conclusion is on pages 30-31.

“Those who know the least”

How this happens is a replay of the long-standing practice that in America those that have the least, or know the least, pay the most for financial services.

The reason for this redistribution is differences in consumers’ financial management savvy. The data “show that reward cards induce more spending, leaving naïve consumers with higher unpaid balances. Naïve consumers also follow a sub-optimal balance-matching heuristic when repaying their credit cards, incurring higher costs.”

The academic work supporting this documented result is summarized in this initial summary:

“Consumers lacking financial sophistication often make costly mistakes. In the consumer credit card market, such behavior can entail over-indebtedness and sub-optimal repayments.

“Banks, in response, can design financial products to exploit these mistakes, combining salient benefits with shrouded payments. Naïve consumers might underestimate these payments and incur costs from usage.

“Sophisticated consumers, in contrast, might rake in the benefits while avoiding the payments and thus profit from usage. Such products can therefore generate an implicit redistribution from naïve to sophisticated consumers and thereby contribute to inequality.”

The cooperative challenge

Members need credit and debit cards for most routine transactions today. The study documents the move away from cash payments. Credit cards are the most common way consumers transact daily and then pay one bill at the end of the charge period. A credit card is as important as a checking account for every consumer.

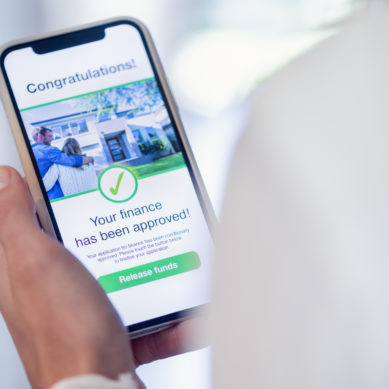

Most consumers are attracted by card rewards. A card with only a low-cost line of credit is a difficult sale against the highly promoted barrage of reward programs. These reward offers are not just from major banks. The most popular cards partner with retail, travel, and other services or products to entice users to accumulate points that can be used to pay future purchases.

Cashback “immediate rewards” offer a 1-3% discount on purchases if points are not a consumer’s goal.

The Federal Reserve study shows that these benefits and rewards programs are paid for by consumers who are less adept at managing their finances. For this user group, the card becomes a loan with interest rates in double digits. This interest income augments interchange fees and is the dominant source of bank card profits.

The Federal Reserve describes these differing consumer card management habits as an income “redistribution from less to more educated, poorer to richer, and high to low minority areas.”

Should credit union card programs be different?

What is a credit union’s responsibility in this wealth transfer process? Should it not offer any rewards card and just maintain a low, universal borrowing rate for all users?

Members want rewards. Is the response to develop multiple card programs to appeal to different segments? Can credit unions really beat the best card offerings by highly visible national programs targeting high-income individuals?

The Federal Reserve study documents what issuers implement as the universal profitability model for credit cards: borrowers pay for the benefits of those who do not carry balances.

With rare exceptions, most credit unions in their credit card offerings follow this banking model. Is this redistribution outcome consistent with cooperative purpose?

This is not a question of legality or even equity. Rather it involves both strategic and values decisions.

If the intent is to serve all members with their diverse needs and circumstances, then marketing efforts will inevitably focus on the largest, strongest, and most financially attractive members. They have bigger cars, larger mortgages, and higher family incomes. This tier is every financial institution’s top priority.

To compete for this wealthier segment’s business with competitive loan and savings rates, the rest of the member base must pay more for loans and earn less on savings. Risk-based pricing is one tool used to implement this redistribution.

But is this the card model coops were intended to provide? I don’t know the answer. Credit unions were originally formed to serve different segments. Today the goal for many is to serve the “whole market.”

The wealthy tend to be excellent rate shoppers. The less well-off tend to take what is offered. Is the result of an open-ended market ambition that no segment is served really well? If so, is such a cooperative strategy sustainable?